May 4, 1997

At the edge of White Canyon in Natural Bridges National Monument in Utah, looking 500 feet down the steep walls of whitish Cedar Mesa sandstone — hiking to the bottom seems an impossibility. Four other realities boggle the mind. First, you’re looking at rock 245 million years old. Secondly, a hardy civilization flourished in this arid canyon for over 1,000 years. Thirdly, this seemingly hostile environment supports an incredible richness of fragile life. Lastly, light snow is falling in early May. The natural mysteries of this timeless place are revealed by geologic layers and the twists and turns of this unforgettable trail down White Canyon.

Two metal staircases and three wooden ladders make the .6-mile descent possible. The trail falls over sloping sandstone to a cliff where a ladder provides access to the next ledge. A giant Douglas fir stands guard. Farther along the ledge, remains of a small shelter lie under an overhang. A spectacular view of Sipapu Bridge appears. Utah serviceberry, Mormon tea, yucca, pinon pine, juniper, and buffalo berry flourish here. Footsteps carved in the sandstone make hiking the next stretch easier. A steep section is negotiated using a handrail.

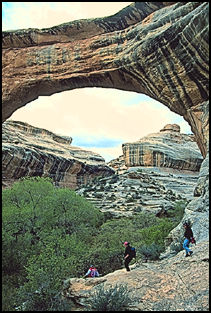

From underneath, Sipapu Bridge is overwhelming, arching 220 feet and spanning 268 feet. An unmaintained, sometimes sandy, sometimes rocky trail follows the wash under the natural arch to Deer Canyon, where beyond, Horsecollar Ruin occupies a southeast-facing alcove. A scramble up slickrock brings you to a fragile, ancient village. However inviting, these fascinating shelters should be approached carefully. Entering a ruin, walking on walls or roofs, or leaning on walls hastens destruction of these magnificent dwellings. As new archaeological techniques are developed, more information about the mysterious, long-ago vanquished denizens may be revealed and shared. People left this area around the year 1270. The dry Utah air has preserved these ruins well, and if you look closely at the mortar, you may see the builder’s fingerprints.

Horsecollar Ruin features a rectangular kiva and two granaries with unusual doors. Instead of rectangular openings, the doors are oval with very smooth mortar, hence the name “horsecollar.” The rectangular kiva, with a nearly intact roof, is typical of the ancient Kayenta culture. Scrambling down to the wash makes you appreciate the former residents’ agility and wonder how young children survived.

A cloudy sky and light snowflakes carried on a chilly wind prompt the realization that at 6,000 feet, life around the canyon 900 years ago was a challenge.

Returning to the trail downstream, cottonwoods tower overhead, with gambel oak, yucca, prickly pear cactus, Indian paintbrush, willow, alder and box elder growing alongside. Pools of water appear occasionally, sheltering various little creatures. Lizards scurry quickly, including the colorful collared lizard. Rattlesnakes also live here, so keep an eye and ear open. Listen for the canyon wren’s musical call or a deer’s movement. Summer thunderstorms in the mountains to the north and east create dangerous flash floods that surge through the canyon, both destroying and nourishing life.

![[Ancient artwork.]](https://cyberwest.com/images/cw12/12glyph.jpg) Kachina Bridge, the youngest in the Monument, appears next, suddenly, along the trail. Its thick arch at 93 feet thick compares to old-timer Owachomo Bridge’s at 9-feet thick. About 245 million years ago this area was beachfront property, complete with sand dunes. As the seas rose, mud and silt buried the dunes.

Kachina Bridge, the youngest in the Monument, appears next, suddenly, along the trail. Its thick arch at 93 feet thick compares to old-timer Owachomo Bridge’s at 9-feet thick. About 245 million years ago this area was beachfront property, complete with sand dunes. As the seas rose, mud and silt buried the dunes.

Over eons, seas retreated, lagoons formed, and desert dunes appeared, turning the original dunes to rock. Later, streams snaked across broad plains. By 10 million years ago, the land was uplifted, increasing stream velocity that cut into the rock, separating the snakelike wiggles with narrow sandstone “fins.” The top layers eroded away revealing the old dunes, now sandstone cliffs. A wet climate between 900 and 4,000 years ago increased water flow that eroded through the fins to create these spectacular natural bridges.

Beneath Kachina Bridge, art carefully etched into the rock surface embellishes the wall.

Turning up Armstrong Canyon, the trail climbs to a shelf avoiding a dropoff — a waterfall during wet times. The trail rejoins the wash. Farther upstream, a rock art panel decorates a cliff. Scrambling up through a million oak leaves, you find building remnants snuggling the wall. Around the corner, unknown stories from hundreds of years ago are chiseled into rock. To the far left are several spirals. A twisting, serpentine figure appears to the right — a snake or perhaps the twists of the canyon, a geologic map of sorts. A humanoid figure with huge four-fingered hands stares from its place. A triangular pattern appears in the middle. Three water striders and a frog-like figure hold unknown meanings. Although anthropologists attempt to interpret rock art, science can never fully explain spiritual Native American insights. We may never know the stories the figures tell.

Proceeding up Armstrong Canyon, the area becomes more arid near the canyon rim. Owachomo Bridge’s graceful, thin span is the smallest and oldest in the area. The bridge is nearing collapse, perhaps in 20 years, perhaps 100 years. A .2 mile hike gaining 180 feet brings you to the road.

To complete the loop, hike about two miles across the mesa through a pinon-juniper forest to the Sipapu Bridge trailhead. The lumpy, black-crusted soil is “crypto,” a composition of cyanobacteria, lichens, mosses, green algae, microfungi and bacteria. This combination holds sand together and provides nutrients in which plants and trees can grow. Crypto is extremely fragile — one footstep can destroy it. Full recovery may take 100 years, leaving the area subject to erosion. Hiking on trails, in washes, and on slickrock preserves the crypto’s life-supporting capabilities.

The 7-mile hike between bridges gives you a first-hand glimpse at nature’s forces, the life’s richness and fragility and makes the visitor wonder how a people utilized the results to live and thrive here — and then disappear.

Story and photos by Maryann Gaug