August 23, 2007

Photo by Blaire Van Valkenburgh, University of California, Los Angeles.

A specialized, highly carnivorous form of gray wolf that lived in Alaska, north of the ice sheets, faced extinction at the end of the Ice Age, a Smithsonian Institution-led team of scientists determined.

This previously unrecognized type of wolf joined other large mammals, including wooly mammoths and saber-toothed cats, in the end-Pleistocene extinction 12,000 years ago.

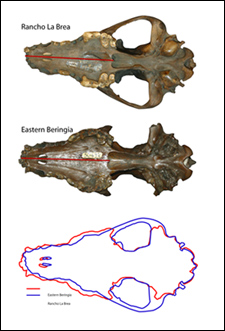

Robust bodies, strong jaws and massive canine teeth for killing large predators characterized the extinct Alaskan wolves, the researchers found.

Wolves were generally thought to have survived the end-Pleistocene mass extinction, although wolves disappeared from northern North America at that time.

A study produced by the team combined genetic and chemical analyses with paleontological study of the morphology, or form, of fossilized skeletal remains. The researchers were able to trace the ancient wolves’ genetic relationships with modern-day wolves, and understand their role in the ancient ecosystem, according to the Smithsonian.

Researchers extracted mitochondrial DNA from fossil wolf bones preserved in permafrost deposits of eastern Beringia and compared the sequences — haplotypes — with those of modern-day wolves in Alaska and elsewhere. The fossils showed a range of haplotypes greater than their modern counterparts.

Unexpectedly, there was no overlap with modern wolves.

“We thought possibly they would be related to Asian wolves instead of American wolves because North America and Asia were connected during that time period,” said study lead author Jennifer Leonard, a research associate with the Smithsonian Genetics Program. “That they were completely unrelated to anything living was quite a surprise.”

“The ancient wolves had relatively more massive teeth and broader skulls with shorter snouts, enhancing their ability to produce strong bites,” said Blaire Van Valkenburgh of the University of California, Los Angeles.

“In addition, the studies of their tooth wear and fracture rate showed high levels of both, consistent with regular and frequent bone-cracking and crunching behavior.”

The lack of corresponding haplotypes between ancient and modern wolves implies that the Alaskan wolves died out completely, leaving no modern descendants. After the extinction, the Alaskan habitat was probably re-colonized by wolves that survived south of the ice sheet in the continental United States, according to Leonard.

The ancient Alaskan wolves differed from modern wolves in their genes, as well as in their skulls and teeth, which were robust and more adapted for forceful bites and shearing flesh than are those of modern wolves. They also showed a higher incidence of broken teeth than living wolves.

Pleistocene wolves likely faced fierce competition for food from formidable competitors, noted Van Valkenburgh, including lions, short-faced bears and saber-tooth cats. During periods of intense competition among predators, modern-day wolves will also consume carcasses more fully, ingesting more bone and eating faster, which increases the risk of tooth fracture.

“Taken together, these features suggest a wolf specialized for killing and consuming relatively large prey, and also possibly habitual scavenging,” Leonard said.

Chemical analyses of the bones support this conclusion. Carbon and nitrogen isotope values of the Alaskan wolf bones are intermediate between those of potential prey species — mammoth, bison, musk ox and caribou — suggesting that their diet was a mix of these large species.

The cause of Pleistocene extinction (called the “megafaunal” extinction because of the large size of many of its victims) is controversial. It has been variously blamed on human hunting or climate change, or on a combination of factors as the Ice Age waned.

For the specialized Alaskan wolves, their demise may be more straightforward. “When their prey disappeared, these wolves did as well,” Leonard said.

The results of the study imply that the effects of the Pleistocene extinction were broader than previously thought. “There may be other extinctions of unique Pleistocene forms yet to be discovered,” Leonard added.

Additionally, the Pleistocene wolf’s extinction may foreshadow the fate of modern specialized predators. Recently, a unique type of nomadic North American gray wolf was discovered. Packs of these wolves migrate across the North American tundra with caribou herds. All other wolves, conversely, are territorial and non-migratory.

“Global warming threatens to eliminate the tundra and it is likely that this will mean the extinction of this important predator,” said Van Valkenburgh.

The team’s study was published in the June 21 online issue of Current Biology.

Sources: Smithsonian Institution, Cell Press.