November 30, 1999

[1 2]

A mile usually doesn’t amount to much in the West. Distances here are measured by the hundreds of miles. It’s easy to look from horizon to horizon in most of west-central Colorado and shiver at the immensity of the barren landscape. A mile is almost meaningless. But the sprawling Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park, straddling the Gunnison River for 14 miles, offers the most exciting, scenic and challenging one-mile trek we’ve encountered.

One of three inner-canyon “hikes” departing from the south rim of the Black Canyon, the Gunnison Route drops a precipitous 1,800 feet in one mile. The absence of a maintained trail for most of the route makes it more of a climb and orienteering adventure than a hike.

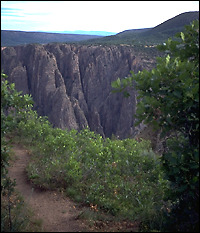

Leading down to the banks of the Gunnison River, the route slowly reveals the stunning beauty of the narrow Black Canyon, framed by towering, sheer walls of metamorphic, layered schist and gneiss rock.

Driving west of the Continental Divide across the heart of Colorado on U.S. 50, the stark plateau past the small town of Gunnison is forbidding — the vegetation sparse, the late-summer sun hot, the wind harsh. From the road, Blue Mesa reservoir and Curecanti National Recreation Area, formed by the damming of the Gunnison River, are naked, exposed bodies of water, the banks stark and treeless — uninviting except to the hardy angler. Geographic features north of Curecanti include Poison Spring Ridge and Deadhorse Gulch, pegging this land as inhospitable to man and beast.

Further downstream, the river has worked quietly over the eons to create a spectacular geologic scene, a gorge both dark and verdant. The 53-mile-long Gunnison, vigilant its ancient quest to meet the mighty Colorado River at Grand Junction, dug deep into the landscape here to carve 12 miles of steep canyon walls that make up the Black Canyon of the Gunnison, the newest U.S. national park.

About 10 miles east of the town of Montrose and six miles north of U.S. 50, the south rim of the Black Canyon of the Gunnison is a hidden oasis that cascades down to the waters of the Gunnison River. This side drainage or “hanging valley” is home to the park’s visitor center, one of its campgrounds (the other is across the river on the north rim), and a meandering road with several lookout points offering views of towering canyon walls and spires.

The south rim campground, at 8,000 feet above sea level, contains dozens of sites and was relatively quiet in late summer. In the middle of a peaceful, fragrant, rolling, scrub and Gambel oak forest sprinkled with sage, the campgrounds are visited often by deer.

From edge of the campgrounds, the Rim Rock Trail is a short, half-mile hike with interpretive sign posts noting various geologic features. The trail hugs the both the road and the canyon rim.

Quickly branching off from the trail, the Uplands Trail winds through thickets of gambel oak, creating a four- to five-foot-high magical canopy through which deer (and presumably, forest sprites) frolic.

Continued –>

[1 2]

A brief history of the Black Canyon

The Black Canyon is the result of volcanic activity, steady downcutting over millions of years by the Gunnison River, and the geologic activities of the Gunnison Uplift and Sawatch and West Elk Mountain ranges. Seasonal floods, rockslides and landslides, and the unyielding flow of the river helped carve this landscape. First establishing its course through soft volcanic rock, the river then cut through to the crystalline rock seen today in the canyon which was thrust up in a formation known as the Gunnison Uplift. It took about two million years for the river to cut the gorge. Prehistoric man and Utes, according the park service, limited their use of the canyon to the rims. Long deemed inaccessible by white men, the need for water in the Uncompahgre Valley in Montrose drove much of the exploration of the canyon in 1900. Nine years later, the Gunnison Diversion Tunnel was finished. The Black Canyon became a national monument in 1933 and a national park this year. |