February 15, 2003

In the Indian Peaks Wilderness west of Ward, Colo., the Brainard Lake area is a wildly popular destination for Colorado hikers. The reason why is obvious. Striking, (usually) snow-capped peaks dominate the area. Moderate and easy trails, though crowded, lead to alpine lakes, rewarding the visitor with plenty of Rocky Mountain splendor without much effort.

In the Indian Peaks Wilderness west of Ward, Colo., the Brainard Lake area is a wildly popular destination for Colorado hikers. The reason why is obvious. Striking, (usually) snow-capped peaks dominate the area. Moderate and easy trails, though crowded, lead to alpine lakes, rewarding the visitor with plenty of Rocky Mountain splendor without much effort.

The route to Brainard is an easy one. Head up Boulder Canyon from Boulder to Nederland, then turn north and drive on Colo. 72 just over 11.5 miles and look for the Brainard Lake sign. Turn left and you’re on your way.

Well-designed parking areas and a one-way road around the lake do much to mitigate the hordes of visitors.

My destination from Brainard Lake on a warm Saturday in late September was Blue Lake, accessed via the Mitchell Lake trail. Another trail, the Mount Audubon trail, also begins from the designated parking area just west of Brainard Lake. Several other trails lead into the Indian Peaks Wilderness from the Brainard Lake area.

The well-maintained trail to Blue Lake is about 3 miles in length and is suitable for most hikers.

The trail begins with a gradual uphill climb. About 10 minutes into the hike, a bridge crosses a small stream. Shortly thereafter, a sign marks the entrance to the Indian Peaks Wilderness. Through the spruce forest to the right, one can see high peaks dotted with snowfields. About one mile in, Mitchell Lake appears off to the right of the trail. A few areas around the lake were closed during my visit for re-vegetation.

Continuing on the now rock-and-boulder-strewn trail, a larger stream appears, and well-placed logs provide access across the water. Past the stream, the trail climbs and traverses a scree field.

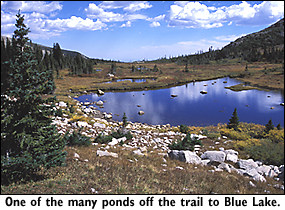

Reaching a small crest, the trail reaches a point where more high peaks rise to the west. A small lake is off to the right of the trail, one of several ponds and lakes that border the trail.

Cutting through boulder fields and crossing another stream, the trail’s destination becomes apparent — a giant wall of stately peaks. Unseen but audible streams flow along the trail with more ponds and small lakes appearing. Further along, the stream tumbles down a boulder field.

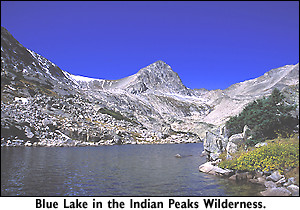

About an hour after embarking on the trail, hiking at a leisurely pace, Blue Lake appears, fed by melting snowfields. A few dozen other hikers were congregating around the lake. At the far side of the lake, a noisy stream rolled into the lake, its sound amplified by the surrounding peaks framing the lake.

According to the U.S. Forest Service, these peaks were named in honor of Colorado’s Native American tribes in 1978 by President Carter, who designated the Indian Peaks as a wilderness area. As recently as 15,000 years ago in geologic time, a glacier covered the area. The permanent snowfields that dot the high country are said to be glacial remnants of the Ice Age. The advancing glaciers scoured out the valleys and basins that mark the area.

According to the U.S. Forest Service, these peaks were named in honor of Colorado’s Native American tribes in 1978 by President Carter, who designated the Indian Peaks as a wilderness area. As recently as 15,000 years ago in geologic time, a glacier covered the area. The permanent snowfields that dot the high country are said to be glacial remnants of the Ice Age. The advancing glaciers scoured out the valleys and basins that mark the area.

As the climate changed and temperatures warmed, the glaciers retreated, depositing jumbled masses of rocks between the peaks. Winter winds sweeping down the slopes and across frozen Brainard Lake caused trees on the east side of the lake to take on so-called “krummholz” forms. Krummholz is a German word for “crooked wood.” The wind-battered trees and stunted shrubs are what one would expect at timberline, normally found at 11,200 feet and higher. The elevation at Brainard Lake is 10,300 feet.

In the summer, the melting snowfields form springs and creeks that flow east from the wilderness, eventually joining the Platte River system

Not a trail for solitude or quiet, the Blue Lake trail nonetheless provides quick and easy access with a forgiving incline into the stunning Indian Peaks high country. However, I wouldn’t consider venturing here in the summer, especially during the weekend.

Story and photos by David Iler