September 25, 2000

[1 2]

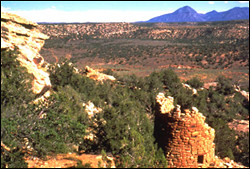

Late in Pueblo II and in early Pueblo III, around 1150 A.D., the size and number of settlements again increased and residential clustering began. Later pueblos were larger multi-storied masonry dwellings with 40 to 50 rooms. For the remainder of Pueblo III (1150-1300 A.D.), major aggregation occurred in the monument, typically at large sites at the heads of canyons. One of these sites includes remains of about 420 rooms, 90 kivas, a great kiva and a plaza – all covering more than 10 acres.

These villages were wrapped around the upper reaches of canyons and spread down onto talus slopes, enclosed year-round springs and reservoirs, and included low, defensive walls. The changes in architecture and site planning reflected a shift from independent households to a communal lifestyle.

Farming during the Puebloan period was influenced by population growth, changing climate and precipitation patterns. As the population grew, the Ancestral Puebloans expanded into increasingly marginal areas. Natural resources were compromised and poor soil and growing conditions made survival increasingly difficult. When dry conditions persisted, Pueblo communities moved to the south, southwest and southeast, where descendants of these Ancestral Puebloan peoples now live.

Soon after the Ancestral Puebloans left the area, the nomadic Ute and Navajo took advantage of the natural diversity found in the variable topography by moving to lower areas, including the monument’s mesas and canyons, during the cooler seasons. A small number of forked stick hogans, brush shelters, and wickiups are signs of this period of occupation.

Structurally part of the Paradox Basin, the landscape is slow to reveal its true nature. From the McElmo Dome in the southern part of the monument, the land slopes gently to the north, giving no indication of the rugged and dissected geology. Rising sharply to the north of McElmo Creek, the McElmo Dome itself is buttressed by sheer sandstone cliffs, with mesa tops rimmed by caprock, and deeply incised canyons.

The monument is home to a variety of wildlife, including the Mesa Verde nightsnake, long-nosed leopard lizard and twin-spotted spiny lizard – all found north of Yellow Jacket Canyon. Peregrine falcons have been observed in the area, as have golden eagles, American kestrels, red-tailed hawks and northern harriers. Game birds like Gamble’s quail and mourning dove are found throughout the monument both in dry, upland habitats and in lush riparian habitat along the canyon bottoms.

According to the BLM, the vast majority of federal lands within the monument have been leased for oil and gas (including carbon dioxide) development, which will continue. Motorized and mechanized vehicle use off-road (except for emergency or authorized administrative purposes) is prohibited.

Discussions regarding protection of this area date back to 1894 when the Salt Lake Times ran a story detailing interest in protecting the region. In 1979, a bill was introduced in Congress to designate the area a National Conservation Area. In the spring of 1999, Interior Secretary Bruce Babbitt began a dialogue with the local communities concerning management and protection of the area.

Discussions regarding protection of this area date back to 1894 when the Salt Lake Times ran a story detailing interest in protecting the region. In 1979, a bill was introduced in Congress to designate the area a National Conservation Area. In the spring of 1999, Interior Secretary Bruce Babbitt began a dialogue with the local communities concerning management and protection of the area.

The local Resource Advisory Council held five public meetings, consulted with local governments and forwarded management recommendations to Babbitt in August 1999. Senator Ben Nighthorse Campbell (R-Colo.) introduced new National Conservation Area legislation in February 2000 (S. 2034), but he suspended action on his bill on March 23, 2000. In May, Secretary Babbitt recommended to President Clinton that the area be designated as a national monument.

Protecting cultural resources

Visitors to Canyons of the Ancients are encouraged to contact the Anasazi Heritage Center before visiting the monument. The Heritage Center is about 10 miles north of Cortez, Colo. at 27501 Highway 184 just west of Dolores, Colo., call 970.882.4811 for more info.

The BLM has issued the following guidelines for visiting the monument:

- Enter sites with a spirit of respect for these places and the significance they hold.

- Stay on existing roads and trails. The desert landscape is fragile and easily damaged.

- Artifacts tell an important story about the past. Please do not dig in sites. If you pick up a pottery piece to look at, please put it back exactly where you found it.

- Walls are fragile. Climbing, standing, or sitting on walls can cause irreparable damage. Please stay off walls, do not move rocks, and do not climb through doorways.

- Bringing offerings to a site changes its story. Please do not add anything to a site.

- Fires can impact a site’s contents and alter the information it has to offer. Please do not build fires or light candles in sites.

- Rock art is very fragile. Oil from even the cleanest hands can damage drawings. Please do not touch rock art.

<– Return to 1

[1 | 2 ]

Special thanks to Roger Alexander of the BLM Southwest Center for photos.