January 14, 2002

Living Rivers and eight other river protection and recreation organizations have called for federal action to address the growing problem of river mud that they say is interfering with boating activities in the upper reaches of Lake Powell in Utah. The groups expressed their sentiments in a letter to the U.S. National Park Service, calling for action to address the sediment problem.

Living Rivers and eight other river protection and recreation organizations have called for federal action to address the growing problem of river mud that they say is interfering with boating activities in the upper reaches of Lake Powell in Utah. The groups expressed their sentiments in a letter to the U.S. National Park Service, calling for action to address the sediment problem.

“This is the beginning of the end for Lake Powell,” says John Weisheit, Living Rivers conservation director and a professional river guide. “People talk about Lake Powell filling with silt sometime in the future, but the future is now.”

Of immediate concern is the slimy muck that threatens the Colorado Plateau’s multimillion-dollar recreational river rafting industry. Similar impacts are being felt downstream in the Grand Canyon, where last summer, the Pearce’s Ferry take-out was closed indefinitely due to sediment clogging the upper reach of Lake Mead Reservoir.

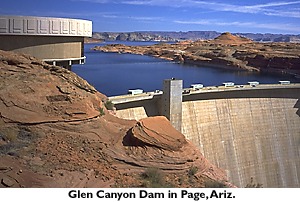

The groups’ letters were sent in response to a NPS redevelopment proposal for Hite Marina, a commercial concession within Glen Canyon National Recreation Area in San Juan County, Utah. The coalition of groups and businesses is asking for the marina project to be put on hold pending a study of sediment-caused access problems, which affect not only boaters on the reservoir but also rafters using the Colorado River’s Cataract Canyon and the lower canyons of the San Juan River. Whitewater trips through both canyons terminate on Lake Powell Reservoir.

Living Rivers is calling for the NPS to undertake a comprehensive sediment study prior to investing more public funds on infrastructure that sediment deposition will, the group contends, ultimately render useless. The Living Rivers’ letter requests the NPS to work with the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation to develop the requested plan and craft an environmental impact statement. The agency has a legal duty, says Living Rivers, to prevent impairment of park resources and provide high-quality recreational opportunities. Yet the Park Service emphasizes reservoir-based, flat water recreation to the detriment of maintaining a world-renowned rafting experience, according to Living Rivers. The rafting industry predates the reservoir’s existence and is dependent on maintaining an open channel from the mouth of Cataract to the take-out at Hite Marina, and from the lower San Juan to Clay Hills Crossing on the reservoir’s San Juan River arm.

Living Rivers warns that access problems already exist at Clay Hills Crossing, and that access to Hite Marina could begin to be curtailed by sediment in as little as two years. Colorado River sediments are quickly filling the bay at Hite and may soon inhibit access to the marina, the terminus for all Cataract Canyon trips.

Living Rivers points out that the NPS, in its 1979 General Management Plan for Glen Canyon NRA, estimated that Hite Marina would have to be abandoned “within thirty years” because of sediment accumulation. The silt arrived ahead of schedule. But despite this predicted event, the agency is moving forward with plans to redevelop the existing marina at its current site.

Sedimentation occurs in all reservoirs, but the problem at Lake Powell is particularly acute, according to Living Rivers. The high silt loads carried by the San Juan and Colorado Rivers are the result of the region’s unique geology. Geologists consider the soils to be among the fastest eroding in the world. Flash floods, common occurrences during the desert’s hot summers, carry huge quantities of silt and debris into surging streams. When these sediment-laden waters reach the still waters of Lake Powell Reservoir, the particles settle out and form unsightly mudflats that at lower water levels can make boat travel impossible.

According to a recent NPS-sponsored study, says Living Rivers, the sediment deposit is quickly advancing toward Hite, and will make the launch ramp there inaccessible within two years whenever the reservoir surface level falls to 3,630 feet above sea level. In 1992, the reservoir dropped to about 3,610 feet. The current level is 3,660 feet.

Sediment at Clay Hills Crossing is already impacting recreational usage. Boaters must often lift and carry their boats and equipment across quicksand-like mud flats to the take-out, creating unsafe conditions for recreationists.

“There’s nothing much they can do but attempt to manage this problem in the near term, but in the long term, decommissioning Glen Canyon Dam is inevitable,” said Weisheit.