September 5, 2001

The summer of 2000 was a hot one in Mesa Verde National Park in southwestern Colorado. Not only was the weather hot and dry, but two lightning-ignited fires roared through forests of pinon pine, Utah juniper and Gambel oak, scorching 21,061 acres in the park and another 7,786 acres nearby. The Bircher Fire in the northeast corner burned from July 20 to July 29. Wetherill Mesa suffered heavy damage from the Pony Fire, which burned from Aug. 2 to Aug. 11. Luckily, the famous prehistoric cliff dwellings and pueblos suffered very little damage.

The summer of 2000 was a hot one in Mesa Verde National Park in southwestern Colorado. Not only was the weather hot and dry, but two lightning-ignited fires roared through forests of pinon pine, Utah juniper and Gambel oak, scorching 21,061 acres in the park and another 7,786 acres nearby. The Bircher Fire in the northeast corner burned from July 20 to July 29. Wetherill Mesa suffered heavy damage from the Pony Fire, which burned from Aug. 2 to Aug. 11. Luckily, the famous prehistoric cliff dwellings and pueblos suffered very little damage.

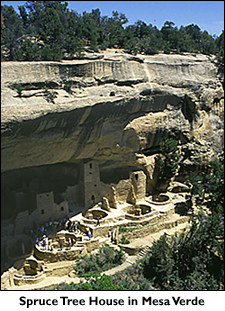

Mesa Verde National Park was established in 1906 for the “preservation … of the sites and other works and relics of prehistoric man … ” and is recognized as a World Heritage Site. Dwellings tucked in cliff alcoves typify the well-preserved ancient structures. Pithouses and pueblos lie spread across the mesa tops. Ancestral Puebloans thrived in this area from about 550 A.D. to 1300 A.D. More than 4,000 prehistoric sites have been identified within the park. Vegetation may still hide others.

Fire is common in Mesa Verde. The Park Point fire lookout receives more lightning strikes than anywhere else except one location in Florida, according to Will Morris, chief of interpretation at Mesa Verde. Much of the vegetation in the park is Gambel oak, pinon and juniper forests. Pinon-juniper forest tends to be fire-resistant. Typically, one tree ignites, less than one acre burns, and the fire puts itself out. However, if conditions are right, the fire will spread, especially if the wind kicks up and tree crowns ignite. Interspersed Gambel oak is very flammable. Since 1906, small fires have been suppressed by humans, probably contributing to the intensity of recent fires by creating an abnormal amount of fuels such as dense forests and tall undergrowth. The park continues its “no-burn” policy because there is only one road in the park and because of the wealth of archaeological sites. Major fires occurred in the park in 1934, 1959, 1972, 1989 and 1996 — all started by lightning.

Ancient inhabitants built their dwellings with sandstone blocks and log beams, and chipped their stories (petroglyphs) into sandstone walls. Fire inside the structures can burn ladders and beams. Packrat middens within sites are very flammable. Intense heat can bake the sandstone until it spalls, or peels off in layers, damaging petroglyphs and building stones.

While the summer 2000 fires raged, archaeologists donned their firefighting gear and accompanied fire crews, scouting for cultural remains as they tried to contain the voracious flames. They recommended locations for fire lines, trying to avoid any sites. If a fire line couldn’t be moved, they hurriedly noted a site’s location. The archaeologists’ knowledge of Mesa Verde’s terrain proved invaluable during firefighting efforts.

Wetherill Mesa suffered the most damage in terms of destruction of modern buildings. The Pony Fire devastated day-use facilities including rest rooms, a ranger station and visitor shelter. Four shelters that protected ancient pithouses and early pueblos were also destroyed, but the sites suffered no damage. The fire threatened several cliff dwellings, but only charred a few ladders in Step House and spalled some rock in the alcove. The ancient building stones remained unharmed. A bridge on the entrance trail was destroyed. At Mug House, the fire reached the alcove’s lip, but didn’t enter the dwellings. The fire burned above Long House, then below, but didn’t enter the alcove itself.

The Bircher Fire burned in some areas that had not been surveyed for archaeological sites. Valiant efforts by firefighters saved Morefield Campground from this fire. Prater Ridge Trail near the campground was scheduled to reopen in mid-summer after trail maintenance work is completed. The Park Point fire lookout was protected before the Bircher Fire raced over it. The lack of fuel in the adjoining area that is recovering from the 1996 fire actually helped end this large fire. About 23,000 acres of wildlife habitat were lost, including some Mexican spotted owl territory on the south end. An errant slurry drop killed fish in the Mancos River. On the positive side, the fire created edge habitat for mountain lions and ravens.

After the conflagration, a U.S. Department of the Interior Burned Area Emergency Rehabilitation (BAER) Team of scientists arrived to analyze the impact of the fires and suppression efforts and to recommend appropriate mitigation to prevent further damage. Their lengthy report documented damage to cultural and natural resources and infrastructure and prescribed rehabilitation measures. Funding of $3.2 million was then provided to Mesa Verde to start the proposed work that will take three to five years to complete. The BAER team also worked with the Ute Mountain tribe to assess the devastation and mitigate damage to soil, wildlife habitat and archaeological sites on the 6,808 acres that burned on their land south of the park. Another $301,000 will help the Utes and U.S. Bureau of Land Management with rehabilitation on their lands. Newly exposed mesa top sites pose the biggest potential problem.

“After a fire, the No. 1 culprit is erosion,” said Morris. “Any rain can erode walls and wash away artifacts taking them out of historical context for archaeologists. Rain can loosen roots of burned trees, which can fall over and knock down dwelling walls.”

An additional 35 archaeologists have been hired to assess damage, document exposed sites, and enter data into a database. After the 1996 Chapin #5 fire, 372 new sites were found. That fire burned close to 5,000 acres. The park anticipates 1,000 new sites may be found after the fires of 2000. In seven weeks in the fall of 2000, treatment crews worked in lower Morefield Canyon and Prater Ridge near Morefield Campground. Telephone and utility cables and two miles of guardrail were replaced. Crews worked on Wetherill Mesa this spring before it opened to the public on Memorial Day weekend.

Mitigation includes installing logs to stop erosion near any unprotected site and recording present status with a goal to stabilize it in its current condition. Building mortar may be replaced and water diverted to prevent flash floods across the site. Any exposed artifacts are documented. If human remains were uncovered by the fire, the crew reburies them in accordance with instructions given by tribal elders. Human remains are usually covered with soil and excelsior.

Morris added that exotic plant species such as Canada thistle and knapweed present a major problem after a fire. They grow in disturbed soil, out-competing native plant species and creating problems for animals dependent on the native plants. The BAER team recommended where to re-seed depending on slope, aspect and growth potential. The team identified appropriate species by location. Native seed, grown at a local nursery, was dropped by helicopter in the fall of 2000. Luckily, a snowstorm quickly followed, which helped soak the seeds into the ground. On Wetherill Mesa, newly seeded grass sprouted this spring. By quickly restoring native vegetation, exotic species will have less chance to become established.

The thick pinon and juniper forest that once blanketed Wetherill Mesa may take up to 300 years to re-grow. The forest will naturally re-seed itself.

The thick pinon and juniper forest that once blanketed Wetherill Mesa may take up to 300 years to re-grow. The forest will naturally re-seed itself.

Gambel oak regenerates from its own root system. Fire may actually stimulate its growth. Already this spring, tender shoots sprouted next to burned bushes, an interesting contrast of green and black.

On Wetherill Mesa, a new visitor shelter, including snack bar, information desk, bookstore and first-aid area, is ready for summer visitors. Shade structures were erected since trees no longer provide an escape from the intense summer sun. The tram is running and tours are being conducted in Step House and Long House. The trail to Nordenskioeld Ruin No. 16 was rebuilt in places.

Fuel reduction programs started in the park in 1993 and will continue. Trees have been thinned to 12-foot spacing not far from park headquarters on Chapin Mesa. Vegetation in front of Spruce Tree House, the best-preserved site in the park, had already been thinned to prevent a fire from entering the alcove and damaging the structures. Ironically, the day Bircher Fire started, a management plan to thin vegetation in front of 23 other cliff dwellings was approved. Typically, dense, high Gambel oak within 20 meters of the alcoves is trimmed, sometimes to root level. After the Pony Fire, where flames stopped at alcove lips, it appeared that thinning near alcoves might not be as critical as first thought. However, reduction will continue to assure the dwellings won’t be endangered by future fires. The Pony Fire was nature’s way of clearing vegetation in front of Step House and Long House.

This summer, on June 30, over 500 lightning strikes hit within a 10-mile radius of Chapin Mesa, location of cliff dwellings and the Chapin Mesa Archaeological Museum, the 30-million object artifact collection. The storm produced no rain, and more than six fires were spotted that evening. Two fires were quickly extinguished. With over 50 percent of the park burned by the 1996 and 2000 fires and with a very dry spring, park fire managers knew a fire on lower Chapin Mesa could quickly endanger visitors, employees, and archaeological artifacts and sites.

A Wildland Fire Situation Analysis was completed, and fuel break was created along the Mesa Verde/Ute Mountain Ute boundary. The park superintendent and Ute Mountain Ute Tribal Council chairman agreed to the recommendation to better protect the visitors, staff and archaeological treasures of both the Ute Mountain Tribal Park and Mesa Verde National Park.

The fuel break will be 400 feet wide and 1.28 miles long between Navajo Canyon and Cliff Canyon. Trees within 50 feet of the park/tribal border will be removed on both sides. In the next 150 feet on both sides, trees will be thinned to a 25-foot spacing. This fireline is designed to provide more options to control future fires.

Mesa Verde National Park’s archaeological treasures were unaffected by the intense fires of summer 2000. In the fire’s wake, a terrific fire ecology classroom has been created. Part of nature’s cycle, fire creates a natural mosaic. Not only can visitors see the world-renowned Ancestral Puebloan sites, but they can also watch nature renewing itself after three major fires in five years.

Story and photos by Maryann Gaug