July 18, 2011

The National Parks Conservation Association released a report analyzing the resource condition of 80 national parks and found that climate change, pollution, invasive species, energy development, adjacent land development and funding shortfalls are impacting wildlife and water and air quality.

The group urged the U.S. federal government to:

- Reintroduce native wildlife

- Implement climate change adaptation and mitigation

- Better manage large landscapes to conserve and restore ecosystems

- Improve the condition of cultural resources

- Incorporate under-represented themes of American history and cultural diversity

NPCA cited both problems and successes in Colorado and Wyoming parks, particularly in Rocky Mountain National Park, Mesa Verde National Park and Yellowstone National Park.

Issues presented by NPCA in its report pertinent to Colorado and Wyoming parks are summarized below.

Native species reintroduction

In Rocky Mountain National Park, the elimination of wolves (to accommodate cattle ranchers), landscape fragmentation and loss of wildlife corridors created an unsustainable population of elk within the park. The National Park Service response, said NPCA, has focused on how to artificially lower the number of elk within park boundaries, instead of reconnecting the park to the surrounding landscape and reintroducing wolves.

After wolves were reintroduced to Yellowstone in 1995, elk numbers decreased and moved away from riverbanks to their original habitat along the base of mountains, allowing new willow and aspen trees to sprout along waterways and bringing back songbirds, beavers and other wildlife and vegetation.

@ Dallas Clemmons

Ecosystem fragmentation

In its report, NPCA referred to the journey of a wolverine through Wyoming and Colorado to illustrate its assertion that better management of large landscapes and the restoration of ecosystems is needed.

In January 2009, a male wolverine in Grand Teton National Park in Wyoming left the park and headed southeast in search of a mate. Wildlife biologists tracking his radio transmitter monitored the animal as it traveled across the sagebrush areas of central Wyoming and through the intact grasslands of the Shirley Basin. The wolverine then passed through the Wind River Indian Reservation.

On Memorial Day weekend, the wolverine is believed to have crossed I-80 into Medicine Bow National Forest. Several weeks later, it entered Colorado and Roosevelt National Forest. In late June, the wolverine arrived in Rocky Mountain National Park, 500 miles south of Grand Teton.

The wolverine’s five-month journey demonstrated the species’ need for large areas of territory and highlighted the importance of the connectivity of the landscape between the two U.S. national parks. Male wolverines stake out breeding territories as large as 500 square miles, and access to adjoining blocks of habitat is crucial to the species’ survival, said NPCA.

Consequently, the group suggested that wolverine conservation should be a multistate effort at the “big landscape” or ecosystem level.

NPCA also cited predator control on lands adjacent to national parks (usually to protect livestock) that removes or kills some animals that migrate through national parks and connected landscapes. Species such as the wolves of Yellowstone and Grand Teton do not recognize park boundaries and are sometimes subject to legal hunting or increased risk of “animal control management” if they wander outside the parks.

Fences also impact park wildlife that migrate seasonally in pursuit of food and habitat, said NPCA. An example is the journey of the pronghorn antelope, which, according to conservation group, makes the longest overland migration in the continental U.S.

A herd of Wyoming pronghorn has moved between winter grounds in the Upper Green River Basin and summer grounds in Grand Teton National Park for more than 6,000 years. However, the number of animals has decreased dramatically and only 300 pronghorn make the biannual trek. Six of the pronghorns’ eight migration corridors have been blocked by livestock fences, natural gas exploration, housing developments and roads, said NPCA.

Managing cultural resources

To help share cultural resource expertise, some parks have forged informal arrangements with other parks.

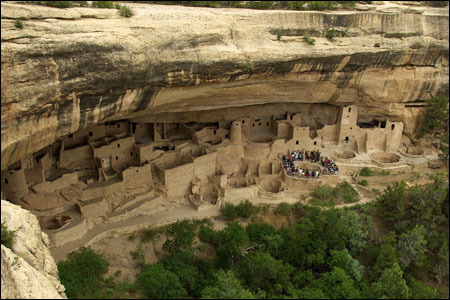

For example, the ruins preservation team from Mesa Verde National Park in Colorado works on projects throughout the Southwest as part of the Vanishing Treasures initiative, a collaboration among park resource managers to preserve prehistoric and historic ruins by obtaining designated project funding and helping preservation specialists train park staff.

Creating a formal system of regionally focused teams of specialists would help address the challenge of making professional expertise available to parks and would enable a concentrated effort needed for historic structure or cultural landscape maintenance, said NPCA.

Parks have also utilized the Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Unit (CESU) national network to help address the erosion of natural and cultural resources. For example, Rocky Mountain National Park used CESU to contract with the historic preservation program of a nearby university to inventory its Mission 66-era structures. The project provided the park with the expertise and staff to complete the inventory.

The Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site in Colorado is also working with researchers from CESU to conduct ethnographic research.

Additionally, Fort Laramie National Historic Site in Wyoming has formed partnerships through CESU to document historic structures and conduct research into construction techniques and materials used at the fort, NPCA pointed out.

The full NPCA report, which addresses issues for parks across the country, may be viewed by visiting the NPCA The State of America’s Parks web page.