November 30, 1999

[1 2]

Onahu Creek/Green Mountain Trails

On the east side of U.S. 34, the Onahu Creek and Green Mountain Trails offer an easy loop — perfect for a casual day hike. From the Onahu trailhead, the trail rolls northeast up and down through tall lodgepole pines, crossing Onahu Creek, then meeting a junction 2.5 miles from the trailhead. To the left is a short spur to Long Meadows; to the right, the trail meanders south to the Continental Divide National Scenic Trail – which traverses east into the heart of the park – and Big Meadows. Along this section of the trail, one may catch glimpses of the Never Summer Mountains across the Kawuneeche Valley to the west.

Big Meadows lives up to its name — it’s a huge grassy expanse, bordered to the southeast by Mount Patterson. An old, crumbling homestead on the edge of Big Meadows provided a picturesque place to stop.

Near the southern edge of Big Meadows, the Green Mountain Trail heads west, along a gradual downhill grade along the course of a small stream. Returning to the Green Mountain trailhead, we encountered several groups of volunteers helping to maintain and upgrade the trail.

Baker Gulch Trail

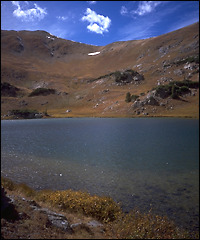

Winding its way into the upper reaches of the Never Summer Range in the Arapaho National Forest, the Baker Gulch Trail delves 4.5 miles deep into alpine splendor to scenic Parika Lake. This trail climbs gradually but relentlessly through a thick pine forest up to a lonely high-altitude terminus at the small lake.

The BGT trailhead is not far from the Kawuneeche Visitor Center and is well-marked. Approaching the trail, the gulch can be seen disappearing into the forest just south of 12,397-foot-high Baker Mountain. On this late-September day, a steady wind pushed fluffy white clouds swiftly across the sky from west to east.

A few hundred yards into the trail, a sign notes the boundary between Rocky Mountain National Park and Arapaho National Forest. Departing quickly from a fast-moving stream, the trail climbs through dense lodgepole pine.

The trail passes a beaver pond, then crosses a boulder field flanked by a large aspen grove that was ablaze with color in late September.

Continuing deeper into the Never Summer Range, the trail crosses the Grand Ditch road, passes green Bowen Mountain before climbing to a narrow but lush meadow. Here, beneath snow-laced mountains, we spotted a dark, solitary figure — a grazing female moose. Alone in this magnificent, green place, the lumbering animal fed quietly on tall bushes. Whatever Zen alpine knowledge or ancestral memories the lonely critter had gathered in its peregrinations we could only imagine. We said a quiet hello and moved on.

Climbing higher, the trail crosses several small streams and lush green meadows before reaching Parika Lake. At approximately 11,500 feet, the temperature lakeside can quickly become chilly. Facing east, the view across Baker Gulch into the heart of Rocky Mountain National Park many miles away more than compensates for the labor to reach Parika Lake.

The hordes of tourists that visit Rocky Mountain National Park travel here for good reason. Many roadside spots offer tremendous views of both mountain scenery and wildlife. However, off the roads and deeper into the forests of the park, that elusive element – solitude – may be found even here.

Story and photos by David Iler

<– Return to Page 1

[1 2]

|

Rocky Mountain National Park ‘at capacity’

With 3,176,582 visitors through October, 1999, Rocky Mountain National Park is on track to break its record of 3,258,921 humans passing through set in 1998. “The park as a whole,” says Peter Allen, park spokesman and management assistant to the superintendent, “is at capacity.” Responding to increasing pressures on park resources, the park service is engaged in two sets of studies. The first involves elk and their effects on lower-level aspen/willow/meadow areas. With about 3,400 elk roaming the eastern side of the park, 60 percent of those leave the boundaries of the park and venture out into the adjacent Estes Valley, says Allen. With herds growing in numbers, the park service is seeking data about the effects on vegetation. Possible remedies include fencing in critical areas, managing herds through contraception, trapping elk and relocating them, and/or adjusting state hunting regulations outside of park boundaries. The re-introduction of predators, such as wolves, is also a possible solution, Allen acknowledges, but he doubts it’s reasonable to expect re-introduction to be seriously considered given the boundaries of the park relative to a wolf’s typical range. The park, Allen adds, is surrounded by fairly well-developed areas, making predator re-introduction, while “providing a more complete ecosystem,” a complex matter. The goal of the study is to determine what the “real conditions are for vegetation and what an ideal population of elk might be,” says Allen. An Environmental Impact Statement will be drawn up, with the public invited to comment sometime next year. Dealing with the park’s traffic congestion is the subject of a second study. The transportation study will focus on the volume of traffic, the level of parking and facilities, and traffic circulating in Estes Park and Estes Valley. Allen assumes one of the recommendations will be increasing and enhancing existing shuttle services along Bear Lake Road. |