February 15, 2003

After five years of preparation, public comment, writing and re-writing, political wrangling, legal battles, and the federal listing of the lynx as a threatened species, the revised White River Forest Plan was released on June 4, 2002.

After five years of preparation, public comment, writing and re-writing, political wrangling, legal battles, and the federal listing of the lynx as a threatened species, the revised White River Forest Plan was released on June 4, 2002.

The newly released plan brought cries of foul from every direction, along with a few compliments. The U.S. Forest Service touted the plan as balanced because “it provides a wide variety of recreation opportunities and forest uses while promoting ecosystem health.” The USFS received and took into account 60,000 comments contained in 14,000 letters, emails and postcards. (A letter may contain more than one comment.)

After the revised plan was released, the public had 90 days until Sept. 5, 2002 to appeal any part of the plan. The USFS received appeals from, among others, the Colorado Off-Highway Vehicle Coalition, a consortium of environmental groups (Aspen Wilderness Workshop, White River Conservation Project, Sierra Club, The Wilderness Society, Center For Native Ecosystems, Colorado Wild and American Lands Alliance), Backcountry Skiers Alliance and Vail Resorts.

The White River National Forest

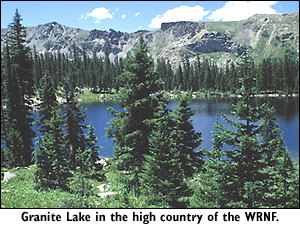

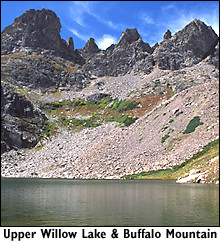

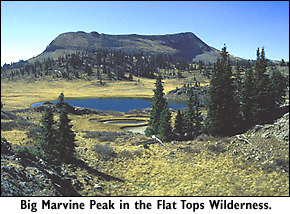

The White River National Forest encompasses 2.3 million acres in north-central Colorado west of the Continental Divide and straddling I-70. It includes one-sixth of national forest system lands in Colorado, but accounts for about 30 percent of recreational use.

Home to the Colorado’s largest elk herd, about 33 percent of the WRNF is designated wilderness. It also hosts 64 percent of downhill skiing in Colorado at 10 ski areas including Aspen and Vail. Backcountry skiers enjoy a system of huts tucked away in beautiful locations. Ranked fifth in the nation in recreational visitor days, the WRNF is popular with skiers, kayakers, hikers, mountain bikers, snowmobilers, all-terrain-vehicle enthusiasts, equestrians, hunters and sightseers.

Forest plan overview

Each national forest is required by law to have a management plan, which is typically revised every 10 to 15 years. The forest plan is a high-level document which assigns management prescriptions, similar to zoning, to the entire forest. The prescriptions indicate what type of uses are or are not allowed. The last White River Forest Plan was completed in 1984 before mountain biking became popular and off-highway vehicles gained powerful engines. Colorado’s population grew by over one million people in that time and several counties within the WRNF reported some of Colorado’s highest growth rates.

During the revision process, everyone wanted a piece of the national forest pie. The USFS and environmentalists promoted forest health and biodiversity — sometimes from different viewpoints. Motorized off-road vehicle users wanted to continue to ride off-road versus the proposed “on designated trails and roads only” designation. Cross-country skiers requested quiet areas while snowmobilers scrambled to maintain their favorite play areas. Mountain bikers raced to add social (user-created) trails to the trail inventory.

After people skimmed the revised plan and then reread it in detail, the contents became clearer.

“The White River Forest Plan is one of the better revised plans we’ve seen in Colorado in the last five years,” said Suzanne Jones, assistant regional director for The Wilderness Society. “This plan recommends 82,000 acres for wilderness designation, 10 times more than three other forest plans combined. Another plus is that anyone on wheels has to stay on designated roads and trails instead of being able to go where (they) want and rut up the land.”

Six existing wilderness areas could be expanded. Two new, stand-alone wildernesses at lower elevations could also be created — Assignation Ridge, 11,800 acres west of Redstone, and Red Table Mountain and Gypsum Creek, 49,800 acres south of Eagle and north of Ruedi Reservoir. However, only the U.S. Congress can designate wilderness areas.

Other positive features listed by various environmental group representatives include eligibility of five rivers for wild and scenic status, designation of five Research Natural Areas, selection of special interest areas such as Camp Hale, Quandary Peak and Independence Pass, and continuance of a ban on logging in old-growth forest.

“The Environmental Impact Statement contains an extensive review of plant and animal species and their viability,” said Colorado Wild’s Rocky Smith. “The Forest Service did a good job.” Others complained the USFS eliminated a requirement to monitor wildlife annually.

The revised plan requires summer motorized and mechanized users to stay on designated trails and roads. Groups of wilderness visitors may consist of no more than 15 humans with a maximum combination of 25 people and pack animals, a potential problem for outfitters and guides. Backcountry skiers thought snowmobiles had too much territory, while the snowmobile community felt they were restricted to small reservation-like areas. Winter motorized appeared to drop from 51 percent to 38 percent of the WRNF.

Some ski areas gained acreage for potential expansion, much to environmentalists’ dismay. Besides a concern for wildlife habitat, ski area expansion is seen as a way to increase real estate sales near and adjacent to the areas.

Logging potential seemed to include almost half the forest, diminishing roadless area protection. The USFS fudged on wording to protect stream flows.

Water issues

“The forest went from a firm goal of protecting 10 percent of forest streams with all legal means, including bypass flow authority, to an unenforceable objective that sounds nice but is less protective than allowed under current Colorado or federal law,” said Melinda Kassen, director of Trout Unlimited’s Colorado Water Project.

“The forest went from a firm goal of protecting 10 percent of forest streams with all legal means, including bypass flow authority, to an unenforceable objective that sounds nice but is less protective than allowed under current Colorado or federal law,” said Melinda Kassen, director of Trout Unlimited’s Colorado Water Project.

At the heart of the stream flow controversy are Sen. Wayne Allard (R-CO) and Rep. Scott McInnis (R-CO) who believe the USFS has few rights with respect to water, especially bypass stream flows. McInnis, whose district includes the WRNF, is also chair of the Congressional House Subcommittee on Forests & Forest Health. He reportedly held meetings (nothing in writing) with the USFS or U.S. Department of Agriculture and convinced them not to include bypass flow wording in the revised forest plan.

Roadless area issues

With President Clinton’s Roadless Area Conservation Rule enjoined by an Idaho District Court judge in May 2001, the USFS could not implement it in the revised forest plan. Instead, roadless areas were split into three groups with about 32 percent slated to “retain their undeveloped character,” 11 percent earmarked to “likely retain some undeveloped characteristics” but allowing some motorized uses, while about 57 percent open to potential timber harvest, road construction, motorized uses and wildlife habitat developments (including logging).

Logging issues

Colorado Wild’s Smith questioned the acreage identified as suitable for logging. “It’s hard to see who they’re serving here, especially since the mill in Olathe has closed,” said Smith. “The White River is much more valuable for beauty, scenery, wildlife and recreation than it ever could be for timber.”

Ski area expansions

The 1984 forest plan showed ski area permit boundaries within potential expansion areas. The draft forest plan, known as Alternative D, restricted ski areas to their existing permit boundaries. Under the revised plan, each ski area permit will be amended to match the expanded management prescription.

Ski areas in Summit County were given virtually everything they requested. Keystone Resort got Independence Mountain while A-Basin gained Montezuma Basin and the Beavers. No aerial transportation corridors were allowed in the plan, squashing possible interconnection of those two areas. Copper Mountain Resort gained the area from Jacque Peak to Guller Creek (nearing Janet’s Cabin, a popular backcountry hut) but lost the area of Stafford, Smith and Wilder Gulches adjacent to Vail Pass and a strip of land east of Colo. 91.

Breckenridge’s border includes Peak 6 to nearly Peak 5 (the ski area presently encompasses Peaks 7 through 10), losing terrain between Peak 5 and Summit High School.

The USFS justified expansion in Summit County to allow flexibility to address current overcrowding and projected skier day increases (8.6 percent by 2010) due to population growth in the Front Range.

“Additional expansions aren’t necessary since ski areas in the White River expanded by nearly 150 percent in the last 15 years, yet skier numbers rose far less dramatically (28 percent) in the same period,” said Jeff Berman of Colorado Wild. Vera Smith, Colorado Mountain Club’s conservation director, believes traffic congestion on I-70 will limit the growth of skier numbers to less than the USFS predictions.

Over in Vail, Benchmark, Mushroom and Commando Bowls were removed from possible expansion to protect critical lynx habitat. Vail gained South Game Creek Bowl instead and is allocated 12,226 acres total. The Aspen ski areas gained some acreage while losing others. Ski Cooper lost acreage that went to snowcat skiing.

Across the WRNF, potential ski area acreage decreased by 41,400 acres from the 1984 plan, mainly by eliminating proposed ski areas that never materialized.

Before any ski area expansions actually take place, plans must be approved through an environmental analysis process including public comments.

The USFS used a new prescription, Forested Landscape Linkages, to connect wilderness areas with each other so forest carnivores and other species can migrate and disperse among large tracts of undeveloped land to assure a good gene pool. In these areas, snowmobiles are restricted to designated routes while summer motorized travel is limited.

Appeals

Appeals to the forest plan cannot be filed for simply the reason parties “don’t like it.” According to Sue Froeschle, WRNF public affairs officer, appeals need to focus on technical details such as contradictions in the plan, and questions regarding process, evaluation, monitoring and data. Various groups use appeals to try to negotiate for a “better” plan or to clarify discrepancies or wording.

Appeals to the forest plan cannot be filed for simply the reason parties “don’t like it.” According to Sue Froeschle, WRNF public affairs officer, appeals need to focus on technical details such as contradictions in the plan, and questions regarding process, evaluation, monitoring and data. Various groups use appeals to try to negotiate for a “better” plan or to clarify discrepancies or wording.

The Colorado Off-Highway Vehicle Coalition said in a statement on its Web site that it filed an appeal of the revised forest plan “because the plan cuts motorized areas by about 25% for no good reason.”

The Backcountry Skiers Alliance filed an appeal to request five changes including monitoring of winter recreational conflicts and how they will be addressed, requesting inclusion of over 10 years of negotiations and work by the Vail Pass Task Force on proper separation of users on Vail Pass, as well as changing allocations of ski area prescriptions “to ensure that current quality backcountry terrain is not lost to ski area expansion.”

According to an article in the Denver Post on Oct. 6, Vail Resorts also appealed the forest plan over the Forested Landscape Linkage prescription for the Jones Gulch area at Keystone Resort and the designation of Game Creek area at the west end of Vail as a roadless area. (However, according to the forest plan, the Game Creek area is in fact Elk & Deer Winter Range, which allows roads with restricted winter and spring use.)

The Post reported that Vail Resorts claimed the designation of Jones Gulch was not designed “to provide security for lynx … but to obstruct ski area operations at an existing resort.” But the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Colorado Division of Wildlife consider the Jones Gulch corridor to be a critical wildlife movement corridor for not only the lynx but for other far-ranging forest animals.

The forested landscape linkage doesn’t even include all of Jones Gulch — the USFS left the side of one ridge that had been in Keystone’s permit area intact for the ski area. And real estate has played a key role in this area. After several proposals to build expensive homes near the base of Jones Gulch, the Summit County Board of County Commissioners, hearing numerous comments from local residents, finally denied the subdivision because of the wildlife corridor. Keystone also proposed building a lift on the ridge next to Jones Gulch. That proposal is in process with the USFS Dillon Ranger District. Locals have questioned the proposal as the lift does not go to the top of the mountain and appears to serve mainly residences in the base area with limited transportation for the general public.

The consortium of environmental groups filed an appeal based on the numerous comments mentioned above plus other concerns. For example, in response to ski area expansions, their appeal states: “The WRNF Plan and Its Decision Documents Fail To Provide Sound Justification For Numerous Plan Decisions, In Violation Of NEPA, NFMA, and Both Acts Implementing Regulations.” The appeal provides details to substantiate the groups’ claim.

With the Bush administration trying to minimize appeals and water down the National Forest Management Act (NFMA) and National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), the result of the environmental appeal remains unknown at this time. The USFS still has time to negotiate the appeals with the appellants, or simply deny or accept them. Any appellant unhappy with the resolution from the USFS could then file a lawsuit.

Travel management

When the USFS released the draft forest plan in August 1999, it also released a draft travel management plan, listing all roads and trails inventoried on national forest land, whether closed or open, noting seasonal restrictions that may apply, and outlining types of use allowed.

Trail users discovered many trails were not listed in the inventory and even USFS personnel admitted mistakes were made. After requests from many frustrated recreationalists, the two plans — the draft forest plan and travel management plan — were separated.

The travel management process started in September 2002, despite possible appeals that, if upheld, would require changes affecting travel management decisions. The process starts with a 60-day “scoping” period during which comments about what should be in the plan are gathered. Comment deadline was Oct. 31, 2002. All comments must adhere to management prescriptions in the revised forest plan.

The USFS will then develop different alternatives and a draft environmental statement which will be released for public comment. After comments are received, a final plan will be developed and released.

The travel management plan is critical for mountain bikers, off-road-vehicle users, dirt bikers and snowmobilers. The process will determine which USFS system roads and trails will remain open. With the new “closed unless signed open” aspect of the forest plan, many “social” or unclassified roads and trails will be closed. An effort will be made to include as many unclassified trails into the system as possible. Most users recognize a need for seasonal closures on some trails and even agree to close some due to environmental damage. The forest plan indicates a willingness to create more loop trails.

“The unclassified roads will be examined for acceptance into the system or for closure-obliteration. In order to become part of the system there more than likely needs to be a need demonstrated and it has to be in a prescription that would allow that use. Also, they need to be examined by the specialists and are subject to public comment prior to acceptance,” said Wendy Haskins, who is coordinating the travel management plan for the USFS.

Hikers and equestrians continue to have access to virtually all of the national forest although some trails may have seasonal restrictions on them. Cross-country skiers are participating in the travel management process to save quiet areas from snowmobiles.

McInnis proposes Colorado wilderness legislation

On Nov. 13, 2002, McInnis introduced H.R. 5722, to designate certain lands in Colorado as wilderness. This bill reflects recommendations for wilderness designation in the revised White River Forest National Forest Plan. Only Congress can designate wilderness areas under the 1964 Wilderness Act.

The bill allows expansion of the Ptarmigan Peak, Raggeds and Hunter-Fryingpan Wilderness areas in the WRNF in McInnis’ district. It also includes wilderness designation for the Red Table Mountain area south of Eagle. However, with all the conditions and exclusions, one wonders if the area will truly be a wilderness area.

For example, the bill excludes several trails: White Creek, Sundell, Sourdough Lake, Muckey Lake, Mount Thomas, Antones and Antones Lake trails, including an area 10 yards to either side of the trails. The Mount Thomas trail in particular follows the ridge of Red Table Mountain, in the heart of the proposed wilderness area. The trail has been used by dirt bikers, and typical wilderness designation would prohibit them. The McInnis bill trail exclusion would allow dirt bikers on Mount Thomas trail.

The bill also prohibits the U.S. Department of Agriculture from imposing bypass or other minimum instream flow requirements within or upstream of the proposed wilderness area.

Story and photos by Maryann Gaug