September 30, 2000

[1 2]

However, local marine biologists from the Monterey Bay Aquarium and Stanford’s Hopkins Marine Station have refuted the coalition’s claims. They argue that ecological conditions, such as global warming and a rising sea otter population, which feeds on invertebrates, account for the decline, if there is one at all. But even they’re not sure — the human impacts on these tide pools have never been studied.

One thing is for sure, humans do tread here and they do strip life from the rocks.

And it’s the Department of Fish and Game’s responsibility to stop it from happening. As with so many law enforcement agencies, Fish and Game officials say they lack the manpower to properly police the highly accessible tide pools, reachable by a number of turnouts off a major Pacific Grove thoroughfare.

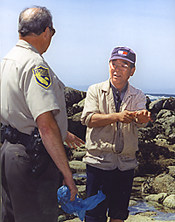

“We’re spread out very thin,” says Ewald, just one of five game wardens for the entire 3,324-square-mile Monterey County, which includes the Los Padres National Forest and 111 miles of mostly undeveloped coastline. Besides policing the coast, Ewald is also responsible for regulating commercial and sport fishing in the bay, and responding to water pollution calls in his 40-hour, no-overtime-allowed week. It comes down to this — Ewald is only able to spend a few hours a week watching over visitors, who insist on plucking precious sea creatures form this special place.

Many of those visitors, whom Ewald calls “inadvertent poachers,” don’t know it’s against the law. Tourists and locals innocently fill up their beach pails with sand and rocks and critters to take home as keepsakes or as new additions to their salt-water aquariums.

Under-supervised school groups visiting the tide pools can sometimes digress into a crew of inadvertent poachers. On one occasion, Ewald recalls pulling a teacher aside to remind him that he and his class were in a protected refuge. “The teacher said, ‘oh no, we’re not taking anything,’ just as a kid walks by with a starfish in his hand.”

Then there are the “hard-core poachers.” They know it’s illegal to take, but they do it anyway, taking home critters to eat, sell, or add to their salt-water aquariums. Poachers that fall into this category will often use poaching tools and are accompanied by lookouts, who warn the collectors of an approaching game warden or police officer.

Later on Sunday, Ewald spots another group collecting illegally, a family filling their colorful plastic pails with tide pools goodies. Obviously, these folks fall into the “inadvertent poachers” category. Ewald approaches the husband and wife with two pre-teen girls, and politely asks to look in their buckets. The family, tourists from Sacramento, has gathered some sand and a handful of hermit crabs in seawater. Ewald explains to them that it’s illegal to take the crabs out of these tide pools, and even if it wasn’t, they’d need a fishing license to do so. “Hundreds of people visit these tide pools everyday. Can you imagine if everyone took home a critter? There’d be nothing left,” he tells them.

The embarrassed husband assures him they will return their catch immediately. But the warden continues his lecture. Even if the animals are put back, he explains, the damage is still done says, because it takes time for the invertebrate to re-attach itself to the rocks. “Their natural protection is to cling to the rocks,” he says. “Even if you put a critter back, it sloshes around and maybe gets eaten by a predator. It’s lost its protection.”

Ewald spares the family a ticket, but it’s a lesson they’re not likely to soon forget.

Story and photos by Laurel Chesky.

<– Return to 1

[1 2]